{William Delaney is one of four men (my mother’s great grandfathers) who arrived in California between the time of the Gold Rush and the 1880s. William, an unsuccessful miner, was left by his wife, who took up with another Irish immigrant, the town butcher. They were accompanied by William’s two youngest daughters. For a time, William raised his oldest daughter Mary Ellen, but he thought it best that she be placed with Moses and Mary Thirston, an older, childless farm couple south of Oroville. It’s been four years since William gave up his daughter.]

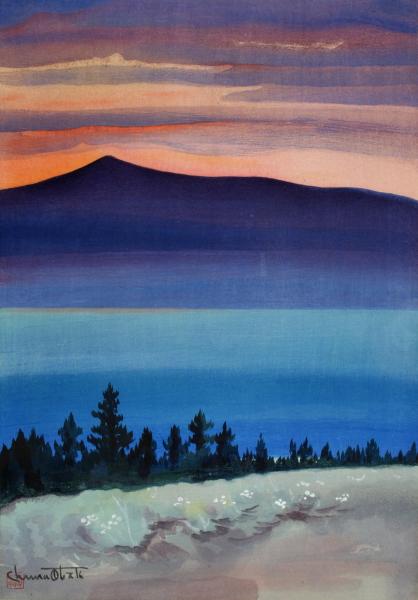

At mid-morning, the sky was cerulean blue with nary a cloud cresting the ridgetops to the east. It was warm, positively springlike, a welcome respite from the Sierra Nevada’s usual winter gray, often with sleet and snow birthed over the churning Pacific.

William Delaney should have been relishing a day like this when his crew was working at altitude on the Oroville Quincy Ridge Road. It was one of those winter rarities – a day on a Sierra mountain pass, five thousand feet above sea level– when the winter cold wouldn’t be boring into his thin leather gloves, making him fearful that one of his digits might snap in two.

Instead, on this morning, his work crew of three was out there unaccompanied, which was seldom a good thing. Hopefully, without his supervision, they were still making progress on improvements to the wagon road following the path of the old Beckwourth Trail towards Virginia City and the Comstock. Without telling his crew why, William was otherwise engaged, rigging up his wagon for one of his infrequent visits to the Thirston Ranch, an hour’s ride south.

William had relocated to a shack on the top of Cherokee, not far from the Spring Valley Hydraulic Mine where some moneyed interests had unearthed gold and diamonds nearly a decade before. Now three shifts of workers were manning hydraulic monitors spewing pressurized water through tunnels and over sluices while others, working under Mr. Edison’s electrified lights, were gathering precious metal and stones under the watchful eyes of the security detail.

William had returned to the first place where he had lived in these parts; almost no one ventured up here then. It was the beforetimes, before he met Ellen Joyce, before little by little, everything had fallen apart.

William’s move up the hill also allowed him blend into the crowd in this new town where hundreds of miners – men younger than he – patronized hastily constructed stores and saloons and a far smaller number of families enrolled their children in its school and worshipped in one of the two churches. The move also enabled William Delaney to stay out of Oroville where he might encounter Moses and Mary Thirston.

When William Delaney had left Mary Ellen with the Thirstons not quite four years before, he fully intended to come for the occasional visit as they had offered. He had seen Moses Thirston on the wooden sidewalk outside the feedstore as that first summer was yielding to fall. “We missed you at the solstice,” were Moses’ first words to him. The encounter grew more cordial with Moses sharing news as to how Mary Ellen was settling in. “She and my Mary like to make pies. Apple and peach.” And there was the sincere offer, “We’ll see you on Thanksgiving then.”

William had nodded and offered Moses a firm handshake. And on Thanksgiving morning – a rare idle day during the week – William had driven his wagon south on the road towards Wyandotte. He could see the Thirston farmhouse on the rise before him. Mary Ellen, in a new gingham dress, was outside with Mary Thirston. Holding a half-peck basket before her, Mary Ellen skipped over to the apple orchard. She placed the basket on the ground by the trunk of the nearest tree and carefully removed a dozen or so Jonathans from the lowest branches. She then raced back to Mary Thirson, displaying her wares. Mrs. Thirston tenderly placed her hand on Mary Ellen’s shoulder as they walked back into the house together.

That’s when William Delaney knew that he would never again visit with his daughter —his little angel. Mary Ellen was skipping. He had never known her to do that; not after the incident. Mary Thirston’s tender touch. That’s what a young girl needed. Not the roughhewn attention of a father, absent from the home from early morning to late afternoon.

William turned the horse around on the country road, being careful not to dip his wagon into the gulleys on either side. As he returned home to Oroville, along with the song of the creaking wagon wheels, the words – chroi briste – echoed in his head. His heart was broken.

Within weeks, William Delaney had moved up the hill to Cherokee.