[William Green Dickinson from the prior scene, three years later.]

Gathered round the dining room table, the entire Dickinson Family had just finished singing “For She’s a Jolly Good Fellow!,” to two-year-old Sarah, who giggled every time there was the slightest pause before the group concluded “which nobody can deny!”

“Mother?” 10-year-old Mary asked, “Do you think Baby Sarah will remember this birthday when she’s older?”

“Well, tell me, what do you remember of Malone?”

William Green Dickinson looked over at his two sons, young men of 21 and 18, whose smiles had dissolved. They had been good sports about the extended family dinner and had even written out a shared card to their youngest sibling without a second prompting.

“I remember the trees and the tulips,” Mary answered.

“Oh, do you now? From before our time in Brooklyn or after?”

William Green Dickinson said, “Boys, you may be excused.”

As soon as their father’s words were spoken, Wallace and George sprung from their chairs, and, without being asked, took their plates into the kitchen. One after the other, they placed them on the counter next to the sink where Maigrete, the comely Swedish servant, was already cleaning up.

William listened to the back steps’ familiar creak and moan as the young men headed to their rooms at the end of the hall. William hoped Wallace wouldn’t roll a cigaret in bed: an infernal habit he had picked up in Montana. While William enjoyed the occasional cigaret or cigar, for him it was a social act, just like sipping sherry before a fine meal or hoisting a brandy after. His son Wallace seemed to need a smoke. And Wallace would often smoke when he drank – whisky mostly – which he threw it back in big gulps. “That’s how they do it in Montana,” his son had told him when he saw William was watching him.

“William, dear?” His wife was looking at him. She appeared to be expecting an answer.

“Yes. Sorry. What is it?”

“Mary asked what is your earliest memory?’

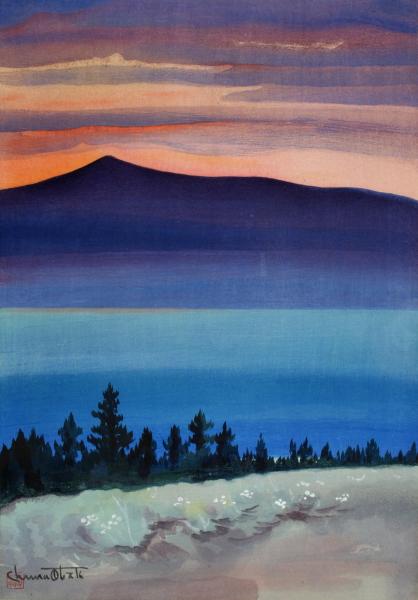

William thought of the small oil painting of his mother [note: she died in childbirth] atop the bureau in his room. He turned to his daughter and said, “Why, tulips and trees, of course!”

Mary beamed, his wife Sarah groaned, Baby Sarah babbled.

“If you ladies don’t mind, I believe I’ll excuse myself and catch up on the day’s news.” Without bothering with his plate, William retreated to the parlor, added a log to the near-dormant fire, and took his position in his favorite chair, his feet quickly warmed by the newly-fired wood.

Before taking a look at the four-page Duluth Tribune, William took a deep breath. Reading The Morning Herald at his desk in the LSM Railroad offices and The Tribune in the parlor, typically before dinner with Sarah and the children, was an absolute necessity. It was the only reliable way he could keep track of the news, which seemed to grow more dreadful by the day, and to try and make sense of what it meant for him.

Oh no, this wasn’t good. A notice to readers right on the front page. Because of declining advertisements, the daily Tribune was moving to a weekly publication. The economic collapse across the country was as severe as it was sudden and William Green Dickinson was in the center of it all. His repeated efforts – first by letter and then by telegram – to reach his brother-in-laws, William Almon Wheeler [member of House of Representatives] and Henry White Belcher [from prior scene], for their counsel had been spectacularly unsuccessful.

William was sweating now, the furnace of bile in his belly firing into his esophagus. He got up from his chair and opened the door to his marble-topped liquor cabinet. He grabbed a rocks glass from the top shelf and, from the lower, removed a blue bottle of the Magnesium Oxide the pharmacist had recommended to quiet the churning in his stomach. Uncorking the bottle, William poured two fingers of the chalky white liquid into the glass. He promptly threw the froth back, like Wallace with whisky, and deposited the glass on the table next to his chair.

William closed his eyes and massaged his temples. He tried to deepen his breaths.

It had been no more than six weeks, but it seemed like an eternity. Jay Cooke, the financier backing the Northern Pacific, had been unable to sell bonds to fund his ambitious plans for a second transcontinental road. Little progress had been made on this road, which was to run all the way to Tacoma on the Puget Sound in Washington Territory. The actual line extended no further than grasslands of Dakota.

[scene continues from here]